Sangrand and Sikhi

By Karminder Singh Dhillon Ph.D (Boston) Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

An increasing number of gurdwara parbhandaks and sangats celebrate the occasion of sangrand.[1] These celebrations take the form of regular kirten, katha and Barah Maha reading type diwans, implying that sangrand is a Sikhi related occasion. A number of justifications are put forth to prove that sangrand is indeed a Sikh function. This article examines these justifications with particular attention to the Gurbanee portions that purportedly discuss and hence dictate sangrand as a Sikh function.

Sangrand originates from the Sanskrit word Sans-kranti (literally: sun-dependent change or sun-related actions). The sun and moon has both been a regular feature of Indian spirituality from the Vedic times. There are gods that correspond to both planets (Sus and Ruv) and many rituals such as baths, fasts, pilgrimages and distributions of charity are tied closely to the positions and movements of these two celestial bodies. The underlying principle of fixing rituals to days on the calendar is that certain days are auspicious, some are bad (therefore activity should be avoided on these days), and others – though inauspicious – can be salvaged by the interventions of spiritual persons or religious chants and rites to turn them into favorable days.

By operational definition, sangrand is the first day of the 12 months[2] that make up the Indian solar calendar. The full moon day on this calendar is called puranmashi, and the moonless night is called masia.

What is the position of Gurbanee and Gurmat on sangrand then? What is the practice of our Gurdwaras in relation to sangrand (and other moon and sun related occasions)? The objective of this article is to explore these questions.

First, the practice of our Gurdwaras. Three broad categories can be observed. The first category observes a diwan on every sangrand. The day is celebrated as an auspicious day. A banee titled Barah-maha (literally: Twelve Months) is recited, the kirtenias sing shabads from this banee that “discuss the particular month”, and the kathakar (if any) proceeds to pick out one of the 14 paragraphs from Barah Maha that “talks about the particular month”, re-reads it, and proceeds to explain it to the sangat. The ardasia (granthi) says in the ardas, words to the effect that the sangat is gathered to celebrate the sangrand of (name of month), asks the Guru to bless the sangat and ensure that the rest of the month passes in happiness. Readers may be interested to note that the Harmandar Complex falls within this first category (done in one of the rooms in the complex).

The second category of gurdwaras doesn’t have a diwan on every sangrand, but would read the Barah Maha on any of their regular Sunday jor-melas, if sangrand happens to coincide. The one particular paragraph that coincides with the month is repeated, and sometimes explained. A good number of smaller gurdwaras within and outside of India fall into this category.

The third category, believed to be a minority does not celebrate or commemorate sangrand. Their position is that Gurmat dictates that no day is good, bad, or worthy of celebration or condemnation simply because it coincides with the position of the Sun or the moon. Sikhs who support such a stand further accept that Barah Maha has nothing to do with sangrand either.

THE JUSTIFICATION. Parbhandaks, sangats and parcharaks who believe that sangrand should be celebrated as a Sikh function provide the following justifications:

(i) Historical: Sangrand has been celebrated since the Vedic days. People always consulted their spiritual echelon on the beginning day of every month to ask for guidance. Sikhs during the days of the Gurus continued to do so. There has never been an injunction for the Sikhs to stop celebrating it.

(ii) Gurmat: The Sikhs asked Guru Arjun Dev ji for advice on how to celebrate sangrand. The Guru proceeded to write the Barah Maha (Majh Mahala 5, GGS pg 133). He told the Sikhs to gather in the Gurdwara and read this Banee on every sangrand.

(iii) Gurbanee: The Barah Maha has one paragraph devoted to each month. Each paragraph therefore is a call for Sikhs to celebrate sangrand. Each paragraph tells the Sikhs how to live the rest of the days of that particular month.

(iv) Logical: Even IF celebrating sangrand is indeed un-gurmat, there is still a logic for the event: sangrand is just an occasion for sangats to meet and pray. It provides an added excuse to come to gurdwara. We don’t have to celebrate sangrand as sangrand. After all, kirten, katha, reading Barah Maha and ardas is all that we do on sangrand day. What can be so un-gurmat about that?

The justification of those gurdwaras in category two above is usually as follows:

(v) Request by sangat. The sangat wants the parbhandaks to instruct the granthi to read Barah Maha on the particular day IF sangrand happens to coincide with whatever normal function the gurdwara is celebrating. The sangat is guru-roop (literally form of the guru), hence its request cannot / should not be turned down.

(vi) Logic: We are merely reading more Banee (Barah Maha). The more Banee we read, the better, isn’t it?

Let us examine each of the six assertions above with a view of not only finding out if any make sense, but if these views are supported or critiqued by Gurbanee – in particular within Barah Maha itself.

Justifications (i) and (ii) are contradictory. If Sikhi was meant to continue following existing practices (of the vedic times), then why did the Sikhs have to go to Guru Arjun ask seek advise on how to celebrate sangrand? Why not just carry on celebrating the “existsing” practice? Besides if the “vedic times” is our basis, then there are a myriad of practices that have to be followed too. We should be throwing water at the sun too – another celebration from the ‘vedic times’.

Justification (ii) is not only based on our ignorance, it further makes out Guru Arjun to be ignorant. Guru Nanak had composed the Barah Maha (Rag Tukhari GGS page 1107). IF it is to be believed that Sikhs did pose the question of “how do we celebrate sangrand” and the Guru’s response was “here, I have written Barah Maha, get together, read, sing, discuss it on every sangrand,” then this answer would have come from Guru Nanak himself. Surely, this would have been the way Guru Nanak himself celebrated sangrand (IF he celebrated it in the first place and IF Barah Maha was written for the purpose of celebrating sangrand) and such “celebration” would automatically have become Sikh practice. In fact IF Barah Maha was written for that purpose of celebrating sangrand, Guru Nanak would have given such instruction upon composing Barah Maha without having the Sikhs ask him.

Accepting this sakhi regarding the 5th Guru telling the Sikhs “here, I have written the Barah Maha, get together and read it” is to suggest that Guru Arjun himself did not know that Guru Nanak had already composed the Barah Maha – a preposterous suggestion relating to a Guru, and regarding one who had compiled the Guru Granth Sahib (Pothee Sahib, then) which contained both Guru Nanak’s Barah Maha and his own).

Alternatively, if indeed, the Sikhs had come to Guru Arjun for advice on how to correctly celebrate sangrand, and indeed if he meant them to gather and read the Barah Maha, his reply would have been: “Guru Nanak has already written Barah Maha, all of you Sikhs should gather and read his Banee.” Alternatively his reply would have been: “but Guru Nanak has already told us how to celebrate sangrand,” or “but we already have an established Sikh practice of how to celebrate sangrand from Guru Nanak’s times that has carried on into Gurus’ Angad, Amardas, and Ramdas ji.” All or any of this replies could, however only have been possible IF the Gurus before him had sanctioned the celebration of Sangrand, and the reading of Guru Nanak’s Barah Maha had become the standard Sikh manner of celebrating sangrand through the periods of the 4 Gurus preceding Guru Arjun.

It is quite obvious hence, that the story of Sikhs going to Guru Arjun to ask “how to celebrate Sangrand” is such that cursory analysis renders its fictitious and exposes its pseudo nature.

So why don’t our sangrandees just change this story and say: the Sikhs went to Guru Nanak and asked for the proper way to celebrate sangrand. And that Guru Nanak replied: “celebrate it by getting together and read, sing and discuss my Barah Maha.” Changing the story solves the problem of not making Guru Arjun appear ignorant, but it still makes our sangrand celebrating folks appear dim-witted. Because when they read the Barah Maha on sangrand day, they read, sing and discuss Guru Arjun’s. If the order was given by Guru Nanak, it would have been to read Guru Nanak’s Barah Maha, not Guru Arjun’s.

There is no doubt that Guru Arjun knew that Guru Nanak had already composed the Barah Maha. IF indeed Barah Maha was written for the purpose of celebrating sangrand, would Guru Arjun compose a second Barah Maha, (thereby creating confusion amongst Sikhs) and then go ahead to say: “read my Barah Maha as part of your sangrand celebration.” IF Guru Nanak had given instructions earlier on to read his Barah Maha, and Sikhs (for whatever reason) came back to Guru Arjun, would he have said “from now on, stop reading Guru Nanak’s Barah Maha on sangrand day, read mine, instead?” It is outrageous to accept that Guru Arjun would set about creating such confusion by issuing ridiculous instructions. IF he had, surely there would be two groups of sangrad celebrating Sikhs today – one reading Guru Nanak’s and the second Guru Arjun’s. There may even be a third group – reading both by justifying – the more banee the better ! So viewed in the context of Barah Maha being sangrand related /connected, Guru Arjun’s decision to compose a second Barah Maha is anything but wise. There cannot be two banees for one the one and same “occasion.”

IF however, Barah Maha is not written for the purpose of celebrating sangrand, has nothing to do with sangrand, and has other higher objectives and spiritual purposes, then the Guru or Gurus could compose two, three or even more Barah Maha Banees. Such multiple Banees with the same name become problematic only if they are tied to an occasion, a celebration on an event; because there can only be one Banee for one event. The very fact that there is a second Barah Maha by Guru Arjun is in itself clear indication that either Barah Maha is not tied to sangrand or any other event, occasion and celebration. In fact Sikhs need to appreciate that no Banee in the entire Guru Granth Sahib is tied to any particular event, occasion and celebration.

Before attempting to understand Barah Maha (both compositions) in its proper context, it is pertinent to look at three underlying Gurmat principles that will help us comprehend the issue.A Sikh needs to understand that the underlying principle of sangrand is simply that certain days – because of the day’s coincidence with the position of the sun (the beginning day of the month in this case) are more auspicious than others. Is there such a principle in gurmat and gurbanee? Second, what does gurmat say about tying/linking a particular banee to a certain event, occasion or celebration. Third, since Barah Maha is associated with “the correct way to celebrate sangrand” what do we make out of the notion of ‘celebrating correctly?’

THREE GURMAT PRINCIPLES WORTH KNOWING.

(a) Auspiciousness. The philosophy of sangrand is rooted in the Bippar principle that that certain days are auspicious and others are not. The latter require spiritual interventions to turn them into favorable days. Sangrand, being the beginning of the calendar month was set as the right time for lay people to go to their spiritual guides (the Brahmin priests) to (i) consult which days and time were auspicious for their specific needs and (ii) get specific advice on what rituals (donations, fasts etc) to perform on the various days of the new month. For the priestly class sangrand served to provide a constant hold and sway on their followers. This was done through an intricate web of instructions valid for the next 30 days (with regular reminders on other occasions such as Masia, Puranmashi etc). Sangrand also served the purpose of providing the priestly classes their regular sustenance. This was done by requesting as donations, whatever material and service were required by the priests themselves for the next 30 days. Sangrand was thus declared doubly auspicious, worth of celebration by the performance of a variety of rituals under the supervision of the bippar priestly class.

Anyone with basic knowledge of Gurmat would know that such philosophy and principles have been critiqued and thus have no place in the daily life of a Sikh. GGS on page 318 has a verse in Gauree Raag composed by Guru Arjun:

Nanak Soee Dinas Suhaavrhaa, Jit Prabh Aavai Chit. Jit Din Visrai Paarbarahm Fit Bhalayree Rut

O Nanak, that day is auspicious, when God comes to mind. Cursed is that day, no matter what the season, when the Supreme Lord God is forgotten.

In another verse (GGS Page 927 Ramkali) Guru Arjun makes the principle crystal clear:

Rutee Maah Moorat Gharaee Gun Uchrat Sobhaavant Jee-o.

Blessed and auspicious is that season, that month, that moment, that hour, when you chant the Lord’s Glorious Praises.

The principle is clear. Days (or hours) are not auspicious or otherwise simply because they are named such or happen to be such or because they coincide with the positions of the sun, moon or other celestial bodies. The beginning of the month is no more or less auspicious than the second, third or 30th day. What makes the moment auspicious is what the Sikh does spiritually during that moment.

It follows therefore that sangrand, massia, puranmashi or Monday or Wednesday, or the 1st or the 31st has no meaning, significance or relevance to a Sikh simply on its own.

(b) Linking Banees with occasions. Sikhs need to appreciate that no Banee in the entire Guru Granth Sahib is tied to any particular event, occasion and celebration. This does not however mean that Sikhs have not (wrongly) tied Banees to occasions. Ramkali Sadd (GGS page 923) has been tied by some Sikhs to be read during the death ceremony. Some gurdwara parbhandaks and granthis recite it, arguing that this banee evokes sad emotions – hence meant for sad occasions. Reciting Ramkali Sadd has thus become a ritual related to death in some gurdwaras. Never mind that this banee is a critique of ritual and a clear call for a Sikh to rise above the sway of emotions. The Gurmat practice of reading the one and same Anand Sahib during all Sikh functions, irrespective of nature (death, birth, joy or otherwise), and the reciting of the same Salok Mahala 9 during every Bhog ceremony (death / birth/joyous/otherwise) is indication of this Gurmat principle. The Sikh Rehat Maryada of Anand Karaj does require the singing of Lavan, but Lavan is not a Banee (as Barah Maha, Ramkali Sadd, Sukhmani or Japji is for instance). The Lavan consists of one single shabad with four parts (Suhee Fourth Guru, GGS pg 773). This shabad is not even titled as Lavan by the Guru. We have given it the title of Lavan (meaning circumambulation). Nothing should stop any Sikh from reading/singing this shabad at any occasion. On one occasion, I have witnessed this Lavan shabad turning out as the Hukumnama after the Ardas during a death ceremony. What better way for the Guru to instill the notion that the Lavan shabad is not reserved for Anand Karaj.

Linking Barah Maha to sangrand is therefore not in accordance with Gurmat. It is an afterthought. Sangrand (and a host of other vedic / bhramanical practices/occasions/events) has obviously been brought in as Sikh practice first and the effort to legitimize, justify, and obfuscate was undertaken much later.

It is fairly obvious that sangrand was smuggled into Sikh gurdwaras by certain elements (mahants, derawads and other deviants) whose only justification was that they owned / ran our gurdwaras and had possession of our parchar for over two centuries after the demise of the tenth Guru. The demand for justification came very much later, when thinking Sikhs started asking for it. The justifications were therefore cooked up by the beneficiary elements (modern day sants, dera fellows, gurmat- illiterate parbhandaks etc) who could not reach any higher than the standards of hey diddle diddle. They had no knowledge of Guru Nanak’s Barah Maha, they had never read (let alone understood) either of the Barah Maha, had no interest in looking beyond the title of these two banees, could not be concerned with thinking through the logic of two Barah Mahas, or that the banee was a critique of everything that sangrand stood for, and had no knowledge whatsoever of the true principles of Gurmat.

All these sangrandees could do was to cook up sakhis of Sikhs going to Gurus, and the Gurus instructing the Sikhs to celebrate this occasion and whatever else that these sants, mahants and deviants had smuggled into our gurdwaras. Their sakhis are essentially “do as you are told, because the Guru told the Sikhs.” Knowing very well, perhaps, that Sikhs rarely make an effort to understand their treasure of gurbanee, these adulterators ventured to link some banee or other to their smuggled practices; never mind if the banee actually condemned that very practice. They linked Gagan Mei Thal Rav Chand Deepak Baney (Dhnasri Guru Nanak: GGS page 66) to their smuggled practice of Aarti in the gurdwaras. And they linked a banee titled Twelve Months to sangrand. The logic of their sakhis and their purported banee link was as bogus as the cow jumping over the moon and the spoon running away with the fiddle. It is such hey didle didle stuff on which the dubious sangrand is linked to the spiritually elevating and Godly throne aspiring banees called Barah Maha. That Sikhs have relegated one of these two jewel-banees (Guru Arjun’s composition) to ritualistic reading during sangrand, and the other (Guru Nanak’s) into absolute obscurity is perhaps the most profound tragedy that has fallen on the Sikh psyche in relation to his spiritual connection with gurbanee.

(c) Celebrating Correctly

These deviants who controlled our Gurdwaras for two centuries went a step further in wanting to authenticate all the rituals and activities that they smuggled into our gurdwaras. They hence came up with the fraudulent notion of “celebrating correctly” or “gurmat way to celebrate” ceremonies that had been discarded in total by our Gurus. How does one “celebrate correctly” some celebration that has been rejected in the first place? Within the benchmark of hey didle diddle the way to do it was fairly straightforward. All that was needed was a cooked up sakhi and a banee with a title or a few phrases that had some mention of the smuggled event. Not a difficult undertaking given that sakhis can be continuously modified to withstand whatever scrutiny that came afterwards, and given that Sikhs were generally loath to read, understand and get to the core messages of banee. The following personal narrative may help illustrate.

While taking issue on celebrating sangrand with a dera-trained granthi of a local gurdwara, I was given a new twist to the sakhi of Sikhs going to Guru Arjun on advice regarding how to celebrate sangrand correctly. This granthi’s take was that the Sikhs told Guru Arjun that Guru Nanak’s Barah Maha was too difficult and complex to read and understand. Guru Arjun hence wrote a simplified version, and from that point on, Guru Arjun’s simplified Barah Maha became standard fare during sangrand celebration. This was clearly a case of modification of a dubious sakhi after specific defects were discovered in the original tale. More importantly, such modification laid bare the continued disregard for the Guru and the banee. To accept this embellished sakhi is to accept that by “agreeing to simplify” Guru Nanak’s Banee, Guru Arjun was implying that Guru Nanak had made a mistake of writing a complex Barah Maha, and that such error needed correcting. Looking at the amount of Sanskrit and Prakrit vocabulary that Guru Arjun used in his Barah Maha, the only conclusion one would arrive (IF one accepts this remixed sakhi) is that the fifth Master agreed that Guru Nanak’s Barah Maha was complex, and went ahead and wrote a second Barah Maha which was equally, if not more complex than the first. These sangrandees need to tell us why Guru Arjun’s so called simplified Barah Maha still has to be explained and interpreted by our kathakars at every sangrand para by para, sangrand after sangrand.

If there was a “correct” way to celebrate sangrand, then there must be a correct way to celebrate puranmashi, massia, karva chauth, teerath, fasting, divali and every thing else that belonged elsewhere. In this way, Sikhs could throw water at the sun too; albeit correctly by simultaneously reading out the banee that critiques/condemns this worthless ritual. The “correct way” for Sikhs to do idol worship may as well be to install the Guru’s idol in our gurdwaras, and worship it while reading, reciting, doing kirten and katha of Bhagat Kabir’s shabad Patee Torey Malni, Patee Patee Jeo. (GGS pg 479). That this shabad critiques idol worship is of no consequence. All that mattered was its reading would gurmatize idol worship. What depths of depravity must Sikhs descend to as a result of us not wanting to understand gurbanee before we realize we are being spiritually duped?

Sikhs must be aware that the terminology for Sikh spiritual celebrations is gurpurab (literally events relating to the Guru). Bhai Gurdas ji captures this spirit: Qurbanee Thinaa Gursikha, Bhae Bhagat Gurpurab Karenday. (I am a sacrifice to the Sikhs who in love and devotion celebrate Gurpurabs). This in line with the gurmat principle that a day is not celebrated or shunned simply because it is full moon, because there is an eclipse, because it is a Thursday, or because it the first of the week, month or year. Such a principle is the crux of Birpran Kee Reet. The crux of gurmat is to celebrate events that connect to our Guru. Anything that connects to Birpran Kee Reet connects to pakhand. But all that connects to our Guru connects us to sachkhand.

UNDERSTANDING BARAH MAHA. As pointed out above, there are two banees with the title “Twelve Months” in the GGS. All 1430 pages of the GGS are in poetic form. The Gurus and Bhagats have displayed vast spiritual creativity in their compositions, messages, illustrations, logic, arguments and reasoning. Such creativity is also amply illustrated in, among other things, the choice of titles and the resulting structures and frameworks of their compositions.

In Rag Majh there is a banee titled Din Raen (Literally: Day and Night) (GGS page 136 Majh Mahala 5 Din Raen). Similarly on page 344 of the GGS there is a bane titled Var (Literally: week). It has 8 paragraphs, for each beginning with the name of the day Somvar (Monday), Mangalvar (Tuesday), Budhvaar (Wednesday) etc. Is the latter banee about the particular days (Monday till Sunday)? The title certainly says so – it is about days. Using the logic of sangrandees, Sikhs should gather in the gurdwaras every week and read/discuss/sing this banee. And the granthi should re-read the paragraph that relates to that particular day – and do a katha on it. This would be “correct way” to practice the vedic tradition whereby people consulted their priest on what could or could not be done on particular days. Tuesday was reserved for the wrath of the gods. Thursday was unfit for washing one’s hair. Friday was for washing off sins by fasting. Saturday was for checking if the priest had enough butter on his plate. Sunday was for discovering if his bed sheet had worn out. By the same logic, then Sikhs should also gather at gurdwaras in the day and in the night and the banee titled Din Raen should be read/sung/interpreted.

The discerning gurbanee reader soon realizes that the banee titled Din Raen has nothing to do with day and night, the banee called Var has nothing to do with Somvar till Shaneevaar, and Barah Maha has nothing to do with twelve months. The messages of these Banees are spiritual, heavenly, Godly and elevating. The level of Godliness contained in the part of Din is the same as Raen. The spirit of heavenliness as contained in the paragraph on Somvar is the same as Budhvar. The spiritual elevation encapsulated in the paragraph of Vaisakh is the same as the one on Maghar, or Chet or Fagan or Poh. And above all, the underlying core message is that by themselves the day, the night, a Monday, a Wednesday, a Mahgar, a Vaisakh and a Chet, a January, an August and a December – are all one and the same. They are the same because the creator made them all. They are the same because it is we mankind who have given them names and divisions. It is mankind again that created “positions” for the sun and moon. It would be foolish to categorize our own divisions and positions as auspicious, as worthy of celebration or as good or bad. What matters is what we do to connect to the higher realms of spirituality and Godliness. The Gurus and Bhagats have used the names of days and months as poetic creativity to structure their compositions. Chet is the name of a month, but in the Barah Maha it is used to denote the linguistic definition of Chet (remembrance).

Chet Govind Aradheay, Hovey Anand Ghana (Barah Maha Guru Arjun)

Remember (chet) and contemplate (aradheay) on God and unlimited Joys will come.

Budvar is the name of a day, but Bhagat Kabir used it to denote the definition of Budh (intellect / thought faculty)

Budhvaar Budh Karey Pargas. Through your intellect, let the light of God illuminate your thought faculty)

The sangrandee will interpret the above two verses as follows: In the month of Chet, contemplate on God and unlimited joys will come. On Wednesday, let the light of God illuminate your intellect. Such interpretation is a mockery. What does one do on Monday? Darken one’s intellect? What about the non-Chet months? No need for contemplation? Or no unlimited joy anymore? Why only in Chet month?

If the point that Barah Maha Banee is not about the 12 months, and Vaar Banee is not about the 7 days, and Din Raen Banee is not about day and night is still not clear, then the following may help.

Elsewhere in the GGS there is a banee titled Pattee Likhee (Literally: the written alphabet). It has one paragraph devoted to each of the 53 then prevailing alphabets. (Rag Asa M: 1 Pattee Likhee GGS page 433). On page 435 there is another banee by Guru Amardas with the same name (Rag Asa M: 3 Pattee). On page 250 there is a banee by Guru Arjun called Bawan Akhree (52 alphabets). On page 340 there is a banee by Bhagat Kabir by the same name (Rag Gauri Purabi Bavan Akhree). Applying the logic of the sangrandees, are we now to say that these banees are about alphabets, that certain alphabets are auspicious (for use in our names for instance), or that certain alphabets are bad, or that certain alphabets require the intervention of certain chants and rituals to make them good. The beauty of these banees lies in the Guru’s and Bhagat’s spiritual creativity. Such ingenuity is so amply illustrated that they are able to advocate a different facet of God and His wonder in each and every one of the 52 alphabets. In one sense therefore the underlying message is that all the 52 alphabets are the same because one can always find something spiritual in each of them and all of them.

By advocating that a banee titled Twelve Months is about celebrating sangrand, the sangrandees have undertaken a great leap of logic. Such logic results if one takes the title and confers a meaning to suit a distortion. The meaning of the title should be inferred from the essence of the banee. On page 917 of the GGS we have a banee titled Anand. One could confer a distorted meaning to it by saying the banee was written for King Anand, or that it was written to express the Guru’s joy after his Anand (wedding) or that it was meant for his son named Anand.. The true meaning of “Anand” as ‘spiritual joy’ can only be inferred from reading and understanding the 40 paragraphs of this banee. The inferred meaning of Sukhmani in terms of ‘spiritual calm’ comes from understanding the 24 astpadees. The conferred (distorted) meaning of Sukhmani is “giver of sukh.” This meaning is distorted because in gurmat sukh and dukh are two sides of the same coin. GGS on page: 57 Sukh Dukh Sam Kar Janeyeh. In Sukhmani : Sukh Dukh Sam Dhristeta. (Sam means equivalent). The Guru could not be saying “sukh and dukh are the same, but then here is one banee (Sukhmani) that will bring you only sukh.”

The meaning of the title ‘Twelve Months” has been conferred by Sangrandees as follows: “sangrand is to be celebrated by Sikhs as an auspicious day on which they need to gather at the gurdwara to get guidance on how to spend the 30 days of a particular month. Now consider this: the word sangrand does NOT appear even once in both Barah Mahas. It does not appear even once in the entire GGS. To talk about 12 Indian months and NOT mention sangrand at all is the strongest critique of sangrand and its philosophy. The names of the 12 months are deployed in poetic manner to cajole the Sikh to link to God The message: “link to God/remember Him/sing His praises ” is the same for all the 12 “months.” Under such circumstances, the inferred meaning of Twelve Months ought to be: remember God irrespective of the month, day or hour. Another inferred meaning is: the months may have different names, but that Guru’s message is one and the same. In each and every one of these names lies a Godly message. Looked at from such perspective, Barah Maha is a banee, just like all other banees, for all occasions, NOT tied to any single day, and above all spiritually enlightening.

THE MESSAGE OF BARAH MAHA. Guru Arjun’s compilation starts with the couplet:

Kiret Karam Key Veecharay, Kar Kirpa Melo Raam. Chaar Kunt Deh Dis Bhramay, Thuk Aiye Prabh Kee Dhamm.

Guru Nanak’s composition begins: Tun Sun Kiret Karam Purab Kamaiya. Ser Ser Sukh Suhama Deh So Tun Bhala.

There is similarity in the words. The verses mean that I have been separated from you on account of my deeds/actions (kiret karam). [Karam means labour.] I have looked for peace and solace everywhere (four directions and 10 continents), and come to you after being exhausted by this search.

Can this be the opening verse of any thing remotely connected to sangrand, let alone a call to celebrate that day? A sangrandee is expecting the Guru to tell him that his suffering is on account of the inauspicious month (and not his actions). He is further expecting the Guru to tell him what to do to turn the inauspicious into the auspicious, or at the very least when (what month, time, day) everything will suddenly become auspicious. But the Guru is telling him, auspiciousness has nothing to do with the time, day, and month. It has all to do with our kiret karam, meaning actions.

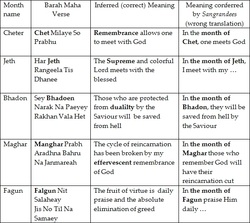

Now let us look at a sampling of the way in which the names of the Indian months are elevated to mean more than just the name of the so called month. The reference to the name of the month is in bold.

An increasing number of gurdwara parbhandaks and sangats celebrate the occasion of sangrand.[1] These celebrations take the form of regular kirten, katha and Barah Maha reading type diwans, implying that sangrand is a Sikhi related occasion. A number of justifications are put forth to prove that sangrand is indeed a Sikh function. This article examines these justifications with particular attention to the Gurbanee portions that purportedly discuss and hence dictate sangrand as a Sikh function.

Sangrand originates from the Sanskrit word Sans-kranti (literally: sun-dependent change or sun-related actions). The sun and moon has both been a regular feature of Indian spirituality from the Vedic times. There are gods that correspond to both planets (Sus and Ruv) and many rituals such as baths, fasts, pilgrimages and distributions of charity are tied closely to the positions and movements of these two celestial bodies. The underlying principle of fixing rituals to days on the calendar is that certain days are auspicious, some are bad (therefore activity should be avoided on these days), and others – though inauspicious – can be salvaged by the interventions of spiritual persons or religious chants and rites to turn them into favorable days.

By operational definition, sangrand is the first day of the 12 months[2] that make up the Indian solar calendar. The full moon day on this calendar is called puranmashi, and the moonless night is called masia.

What is the position of Gurbanee and Gurmat on sangrand then? What is the practice of our Gurdwaras in relation to sangrand (and other moon and sun related occasions)? The objective of this article is to explore these questions.

First, the practice of our Gurdwaras. Three broad categories can be observed. The first category observes a diwan on every sangrand. The day is celebrated as an auspicious day. A banee titled Barah-maha (literally: Twelve Months) is recited, the kirtenias sing shabads from this banee that “discuss the particular month”, and the kathakar (if any) proceeds to pick out one of the 14 paragraphs from Barah Maha that “talks about the particular month”, re-reads it, and proceeds to explain it to the sangat. The ardasia (granthi) says in the ardas, words to the effect that the sangat is gathered to celebrate the sangrand of (name of month), asks the Guru to bless the sangat and ensure that the rest of the month passes in happiness. Readers may be interested to note that the Harmandar Complex falls within this first category (done in one of the rooms in the complex).

The second category of gurdwaras doesn’t have a diwan on every sangrand, but would read the Barah Maha on any of their regular Sunday jor-melas, if sangrand happens to coincide. The one particular paragraph that coincides with the month is repeated, and sometimes explained. A good number of smaller gurdwaras within and outside of India fall into this category.

The third category, believed to be a minority does not celebrate or commemorate sangrand. Their position is that Gurmat dictates that no day is good, bad, or worthy of celebration or condemnation simply because it coincides with the position of the Sun or the moon. Sikhs who support such a stand further accept that Barah Maha has nothing to do with sangrand either.

THE JUSTIFICATION. Parbhandaks, sangats and parcharaks who believe that sangrand should be celebrated as a Sikh function provide the following justifications:

(i) Historical: Sangrand has been celebrated since the Vedic days. People always consulted their spiritual echelon on the beginning day of every month to ask for guidance. Sikhs during the days of the Gurus continued to do so. There has never been an injunction for the Sikhs to stop celebrating it.

(ii) Gurmat: The Sikhs asked Guru Arjun Dev ji for advice on how to celebrate sangrand. The Guru proceeded to write the Barah Maha (Majh Mahala 5, GGS pg 133). He told the Sikhs to gather in the Gurdwara and read this Banee on every sangrand.

(iii) Gurbanee: The Barah Maha has one paragraph devoted to each month. Each paragraph therefore is a call for Sikhs to celebrate sangrand. Each paragraph tells the Sikhs how to live the rest of the days of that particular month.

(iv) Logical: Even IF celebrating sangrand is indeed un-gurmat, there is still a logic for the event: sangrand is just an occasion for sangats to meet and pray. It provides an added excuse to come to gurdwara. We don’t have to celebrate sangrand as sangrand. After all, kirten, katha, reading Barah Maha and ardas is all that we do on sangrand day. What can be so un-gurmat about that?

The justification of those gurdwaras in category two above is usually as follows:

(v) Request by sangat. The sangat wants the parbhandaks to instruct the granthi to read Barah Maha on the particular day IF sangrand happens to coincide with whatever normal function the gurdwara is celebrating. The sangat is guru-roop (literally form of the guru), hence its request cannot / should not be turned down.

(vi) Logic: We are merely reading more Banee (Barah Maha). The more Banee we read, the better, isn’t it?

Let us examine each of the six assertions above with a view of not only finding out if any make sense, but if these views are supported or critiqued by Gurbanee – in particular within Barah Maha itself.

Justifications (i) and (ii) are contradictory. If Sikhi was meant to continue following existing practices (of the vedic times), then why did the Sikhs have to go to Guru Arjun ask seek advise on how to celebrate sangrand? Why not just carry on celebrating the “existsing” practice? Besides if the “vedic times” is our basis, then there are a myriad of practices that have to be followed too. We should be throwing water at the sun too – another celebration from the ‘vedic times’.

Justification (ii) is not only based on our ignorance, it further makes out Guru Arjun to be ignorant. Guru Nanak had composed the Barah Maha (Rag Tukhari GGS page 1107). IF it is to be believed that Sikhs did pose the question of “how do we celebrate sangrand” and the Guru’s response was “here, I have written Barah Maha, get together, read, sing, discuss it on every sangrand,” then this answer would have come from Guru Nanak himself. Surely, this would have been the way Guru Nanak himself celebrated sangrand (IF he celebrated it in the first place and IF Barah Maha was written for the purpose of celebrating sangrand) and such “celebration” would automatically have become Sikh practice. In fact IF Barah Maha was written for that purpose of celebrating sangrand, Guru Nanak would have given such instruction upon composing Barah Maha without having the Sikhs ask him.

Accepting this sakhi regarding the 5th Guru telling the Sikhs “here, I have written the Barah Maha, get together and read it” is to suggest that Guru Arjun himself did not know that Guru Nanak had already composed the Barah Maha – a preposterous suggestion relating to a Guru, and regarding one who had compiled the Guru Granth Sahib (Pothee Sahib, then) which contained both Guru Nanak’s Barah Maha and his own).

Alternatively, if indeed, the Sikhs had come to Guru Arjun for advice on how to correctly celebrate sangrand, and indeed if he meant them to gather and read the Barah Maha, his reply would have been: “Guru Nanak has already written Barah Maha, all of you Sikhs should gather and read his Banee.” Alternatively his reply would have been: “but Guru Nanak has already told us how to celebrate sangrand,” or “but we already have an established Sikh practice of how to celebrate sangrand from Guru Nanak’s times that has carried on into Gurus’ Angad, Amardas, and Ramdas ji.” All or any of this replies could, however only have been possible IF the Gurus before him had sanctioned the celebration of Sangrand, and the reading of Guru Nanak’s Barah Maha had become the standard Sikh manner of celebrating sangrand through the periods of the 4 Gurus preceding Guru Arjun.

It is quite obvious hence, that the story of Sikhs going to Guru Arjun to ask “how to celebrate Sangrand” is such that cursory analysis renders its fictitious and exposes its pseudo nature.

So why don’t our sangrandees just change this story and say: the Sikhs went to Guru Nanak and asked for the proper way to celebrate sangrand. And that Guru Nanak replied: “celebrate it by getting together and read, sing and discuss my Barah Maha.” Changing the story solves the problem of not making Guru Arjun appear ignorant, but it still makes our sangrand celebrating folks appear dim-witted. Because when they read the Barah Maha on sangrand day, they read, sing and discuss Guru Arjun’s. If the order was given by Guru Nanak, it would have been to read Guru Nanak’s Barah Maha, not Guru Arjun’s.

There is no doubt that Guru Arjun knew that Guru Nanak had already composed the Barah Maha. IF indeed Barah Maha was written for the purpose of celebrating sangrand, would Guru Arjun compose a second Barah Maha, (thereby creating confusion amongst Sikhs) and then go ahead to say: “read my Barah Maha as part of your sangrand celebration.” IF Guru Nanak had given instructions earlier on to read his Barah Maha, and Sikhs (for whatever reason) came back to Guru Arjun, would he have said “from now on, stop reading Guru Nanak’s Barah Maha on sangrand day, read mine, instead?” It is outrageous to accept that Guru Arjun would set about creating such confusion by issuing ridiculous instructions. IF he had, surely there would be two groups of sangrad celebrating Sikhs today – one reading Guru Nanak’s and the second Guru Arjun’s. There may even be a third group – reading both by justifying – the more banee the better ! So viewed in the context of Barah Maha being sangrand related /connected, Guru Arjun’s decision to compose a second Barah Maha is anything but wise. There cannot be two banees for one the one and same “occasion.”

IF however, Barah Maha is not written for the purpose of celebrating sangrand, has nothing to do with sangrand, and has other higher objectives and spiritual purposes, then the Guru or Gurus could compose two, three or even more Barah Maha Banees. Such multiple Banees with the same name become problematic only if they are tied to an occasion, a celebration on an event; because there can only be one Banee for one event. The very fact that there is a second Barah Maha by Guru Arjun is in itself clear indication that either Barah Maha is not tied to sangrand or any other event, occasion and celebration. In fact Sikhs need to appreciate that no Banee in the entire Guru Granth Sahib is tied to any particular event, occasion and celebration.

Before attempting to understand Barah Maha (both compositions) in its proper context, it is pertinent to look at three underlying Gurmat principles that will help us comprehend the issue.A Sikh needs to understand that the underlying principle of sangrand is simply that certain days – because of the day’s coincidence with the position of the sun (the beginning day of the month in this case) are more auspicious than others. Is there such a principle in gurmat and gurbanee? Second, what does gurmat say about tying/linking a particular banee to a certain event, occasion or celebration. Third, since Barah Maha is associated with “the correct way to celebrate sangrand” what do we make out of the notion of ‘celebrating correctly?’

THREE GURMAT PRINCIPLES WORTH KNOWING.

(a) Auspiciousness. The philosophy of sangrand is rooted in the Bippar principle that that certain days are auspicious and others are not. The latter require spiritual interventions to turn them into favorable days. Sangrand, being the beginning of the calendar month was set as the right time for lay people to go to their spiritual guides (the Brahmin priests) to (i) consult which days and time were auspicious for their specific needs and (ii) get specific advice on what rituals (donations, fasts etc) to perform on the various days of the new month. For the priestly class sangrand served to provide a constant hold and sway on their followers. This was done through an intricate web of instructions valid for the next 30 days (with regular reminders on other occasions such as Masia, Puranmashi etc). Sangrand also served the purpose of providing the priestly classes their regular sustenance. This was done by requesting as donations, whatever material and service were required by the priests themselves for the next 30 days. Sangrand was thus declared doubly auspicious, worth of celebration by the performance of a variety of rituals under the supervision of the bippar priestly class.

Anyone with basic knowledge of Gurmat would know that such philosophy and principles have been critiqued and thus have no place in the daily life of a Sikh. GGS on page 318 has a verse in Gauree Raag composed by Guru Arjun:

Nanak Soee Dinas Suhaavrhaa, Jit Prabh Aavai Chit. Jit Din Visrai Paarbarahm Fit Bhalayree Rut

O Nanak, that day is auspicious, when God comes to mind. Cursed is that day, no matter what the season, when the Supreme Lord God is forgotten.

In another verse (GGS Page 927 Ramkali) Guru Arjun makes the principle crystal clear:

Rutee Maah Moorat Gharaee Gun Uchrat Sobhaavant Jee-o.

Blessed and auspicious is that season, that month, that moment, that hour, when you chant the Lord’s Glorious Praises.

The principle is clear. Days (or hours) are not auspicious or otherwise simply because they are named such or happen to be such or because they coincide with the positions of the sun, moon or other celestial bodies. The beginning of the month is no more or less auspicious than the second, third or 30th day. What makes the moment auspicious is what the Sikh does spiritually during that moment.

It follows therefore that sangrand, massia, puranmashi or Monday or Wednesday, or the 1st or the 31st has no meaning, significance or relevance to a Sikh simply on its own.

(b) Linking Banees with occasions. Sikhs need to appreciate that no Banee in the entire Guru Granth Sahib is tied to any particular event, occasion and celebration. This does not however mean that Sikhs have not (wrongly) tied Banees to occasions. Ramkali Sadd (GGS page 923) has been tied by some Sikhs to be read during the death ceremony. Some gurdwara parbhandaks and granthis recite it, arguing that this banee evokes sad emotions – hence meant for sad occasions. Reciting Ramkali Sadd has thus become a ritual related to death in some gurdwaras. Never mind that this banee is a critique of ritual and a clear call for a Sikh to rise above the sway of emotions. The Gurmat practice of reading the one and same Anand Sahib during all Sikh functions, irrespective of nature (death, birth, joy or otherwise), and the reciting of the same Salok Mahala 9 during every Bhog ceremony (death / birth/joyous/otherwise) is indication of this Gurmat principle. The Sikh Rehat Maryada of Anand Karaj does require the singing of Lavan, but Lavan is not a Banee (as Barah Maha, Ramkali Sadd, Sukhmani or Japji is for instance). The Lavan consists of one single shabad with four parts (Suhee Fourth Guru, GGS pg 773). This shabad is not even titled as Lavan by the Guru. We have given it the title of Lavan (meaning circumambulation). Nothing should stop any Sikh from reading/singing this shabad at any occasion. On one occasion, I have witnessed this Lavan shabad turning out as the Hukumnama after the Ardas during a death ceremony. What better way for the Guru to instill the notion that the Lavan shabad is not reserved for Anand Karaj.

Linking Barah Maha to sangrand is therefore not in accordance with Gurmat. It is an afterthought. Sangrand (and a host of other vedic / bhramanical practices/occasions/events) has obviously been brought in as Sikh practice first and the effort to legitimize, justify, and obfuscate was undertaken much later.

It is fairly obvious that sangrand was smuggled into Sikh gurdwaras by certain elements (mahants, derawads and other deviants) whose only justification was that they owned / ran our gurdwaras and had possession of our parchar for over two centuries after the demise of the tenth Guru. The demand for justification came very much later, when thinking Sikhs started asking for it. The justifications were therefore cooked up by the beneficiary elements (modern day sants, dera fellows, gurmat- illiterate parbhandaks etc) who could not reach any higher than the standards of hey diddle diddle. They had no knowledge of Guru Nanak’s Barah Maha, they had never read (let alone understood) either of the Barah Maha, had no interest in looking beyond the title of these two banees, could not be concerned with thinking through the logic of two Barah Mahas, or that the banee was a critique of everything that sangrand stood for, and had no knowledge whatsoever of the true principles of Gurmat.

All these sangrandees could do was to cook up sakhis of Sikhs going to Gurus, and the Gurus instructing the Sikhs to celebrate this occasion and whatever else that these sants, mahants and deviants had smuggled into our gurdwaras. Their sakhis are essentially “do as you are told, because the Guru told the Sikhs.” Knowing very well, perhaps, that Sikhs rarely make an effort to understand their treasure of gurbanee, these adulterators ventured to link some banee or other to their smuggled practices; never mind if the banee actually condemned that very practice. They linked Gagan Mei Thal Rav Chand Deepak Baney (Dhnasri Guru Nanak: GGS page 66) to their smuggled practice of Aarti in the gurdwaras. And they linked a banee titled Twelve Months to sangrand. The logic of their sakhis and their purported banee link was as bogus as the cow jumping over the moon and the spoon running away with the fiddle. It is such hey didle didle stuff on which the dubious sangrand is linked to the spiritually elevating and Godly throne aspiring banees called Barah Maha. That Sikhs have relegated one of these two jewel-banees (Guru Arjun’s composition) to ritualistic reading during sangrand, and the other (Guru Nanak’s) into absolute obscurity is perhaps the most profound tragedy that has fallen on the Sikh psyche in relation to his spiritual connection with gurbanee.

(c) Celebrating Correctly

These deviants who controlled our Gurdwaras for two centuries went a step further in wanting to authenticate all the rituals and activities that they smuggled into our gurdwaras. They hence came up with the fraudulent notion of “celebrating correctly” or “gurmat way to celebrate” ceremonies that had been discarded in total by our Gurus. How does one “celebrate correctly” some celebration that has been rejected in the first place? Within the benchmark of hey didle diddle the way to do it was fairly straightforward. All that was needed was a cooked up sakhi and a banee with a title or a few phrases that had some mention of the smuggled event. Not a difficult undertaking given that sakhis can be continuously modified to withstand whatever scrutiny that came afterwards, and given that Sikhs were generally loath to read, understand and get to the core messages of banee. The following personal narrative may help illustrate.

While taking issue on celebrating sangrand with a dera-trained granthi of a local gurdwara, I was given a new twist to the sakhi of Sikhs going to Guru Arjun on advice regarding how to celebrate sangrand correctly. This granthi’s take was that the Sikhs told Guru Arjun that Guru Nanak’s Barah Maha was too difficult and complex to read and understand. Guru Arjun hence wrote a simplified version, and from that point on, Guru Arjun’s simplified Barah Maha became standard fare during sangrand celebration. This was clearly a case of modification of a dubious sakhi after specific defects were discovered in the original tale. More importantly, such modification laid bare the continued disregard for the Guru and the banee. To accept this embellished sakhi is to accept that by “agreeing to simplify” Guru Nanak’s Banee, Guru Arjun was implying that Guru Nanak had made a mistake of writing a complex Barah Maha, and that such error needed correcting. Looking at the amount of Sanskrit and Prakrit vocabulary that Guru Arjun used in his Barah Maha, the only conclusion one would arrive (IF one accepts this remixed sakhi) is that the fifth Master agreed that Guru Nanak’s Barah Maha was complex, and went ahead and wrote a second Barah Maha which was equally, if not more complex than the first. These sangrandees need to tell us why Guru Arjun’s so called simplified Barah Maha still has to be explained and interpreted by our kathakars at every sangrand para by para, sangrand after sangrand.

If there was a “correct” way to celebrate sangrand, then there must be a correct way to celebrate puranmashi, massia, karva chauth, teerath, fasting, divali and every thing else that belonged elsewhere. In this way, Sikhs could throw water at the sun too; albeit correctly by simultaneously reading out the banee that critiques/condemns this worthless ritual. The “correct way” for Sikhs to do idol worship may as well be to install the Guru’s idol in our gurdwaras, and worship it while reading, reciting, doing kirten and katha of Bhagat Kabir’s shabad Patee Torey Malni, Patee Patee Jeo. (GGS pg 479). That this shabad critiques idol worship is of no consequence. All that mattered was its reading would gurmatize idol worship. What depths of depravity must Sikhs descend to as a result of us not wanting to understand gurbanee before we realize we are being spiritually duped?

Sikhs must be aware that the terminology for Sikh spiritual celebrations is gurpurab (literally events relating to the Guru). Bhai Gurdas ji captures this spirit: Qurbanee Thinaa Gursikha, Bhae Bhagat Gurpurab Karenday. (I am a sacrifice to the Sikhs who in love and devotion celebrate Gurpurabs). This in line with the gurmat principle that a day is not celebrated or shunned simply because it is full moon, because there is an eclipse, because it is a Thursday, or because it the first of the week, month or year. Such a principle is the crux of Birpran Kee Reet. The crux of gurmat is to celebrate events that connect to our Guru. Anything that connects to Birpran Kee Reet connects to pakhand. But all that connects to our Guru connects us to sachkhand.

UNDERSTANDING BARAH MAHA. As pointed out above, there are two banees with the title “Twelve Months” in the GGS. All 1430 pages of the GGS are in poetic form. The Gurus and Bhagats have displayed vast spiritual creativity in their compositions, messages, illustrations, logic, arguments and reasoning. Such creativity is also amply illustrated in, among other things, the choice of titles and the resulting structures and frameworks of their compositions.

In Rag Majh there is a banee titled Din Raen (Literally: Day and Night) (GGS page 136 Majh Mahala 5 Din Raen). Similarly on page 344 of the GGS there is a bane titled Var (Literally: week). It has 8 paragraphs, for each beginning with the name of the day Somvar (Monday), Mangalvar (Tuesday), Budhvaar (Wednesday) etc. Is the latter banee about the particular days (Monday till Sunday)? The title certainly says so – it is about days. Using the logic of sangrandees, Sikhs should gather in the gurdwaras every week and read/discuss/sing this banee. And the granthi should re-read the paragraph that relates to that particular day – and do a katha on it. This would be “correct way” to practice the vedic tradition whereby people consulted their priest on what could or could not be done on particular days. Tuesday was reserved for the wrath of the gods. Thursday was unfit for washing one’s hair. Friday was for washing off sins by fasting. Saturday was for checking if the priest had enough butter on his plate. Sunday was for discovering if his bed sheet had worn out. By the same logic, then Sikhs should also gather at gurdwaras in the day and in the night and the banee titled Din Raen should be read/sung/interpreted.

The discerning gurbanee reader soon realizes that the banee titled Din Raen has nothing to do with day and night, the banee called Var has nothing to do with Somvar till Shaneevaar, and Barah Maha has nothing to do with twelve months. The messages of these Banees are spiritual, heavenly, Godly and elevating. The level of Godliness contained in the part of Din is the same as Raen. The spirit of heavenliness as contained in the paragraph on Somvar is the same as Budhvar. The spiritual elevation encapsulated in the paragraph of Vaisakh is the same as the one on Maghar, or Chet or Fagan or Poh. And above all, the underlying core message is that by themselves the day, the night, a Monday, a Wednesday, a Mahgar, a Vaisakh and a Chet, a January, an August and a December – are all one and the same. They are the same because the creator made them all. They are the same because it is we mankind who have given them names and divisions. It is mankind again that created “positions” for the sun and moon. It would be foolish to categorize our own divisions and positions as auspicious, as worthy of celebration or as good or bad. What matters is what we do to connect to the higher realms of spirituality and Godliness. The Gurus and Bhagats have used the names of days and months as poetic creativity to structure their compositions. Chet is the name of a month, but in the Barah Maha it is used to denote the linguistic definition of Chet (remembrance).

Chet Govind Aradheay, Hovey Anand Ghana (Barah Maha Guru Arjun)

Remember (chet) and contemplate (aradheay) on God and unlimited Joys will come.

Budvar is the name of a day, but Bhagat Kabir used it to denote the definition of Budh (intellect / thought faculty)

Budhvaar Budh Karey Pargas. Through your intellect, let the light of God illuminate your thought faculty)

The sangrandee will interpret the above two verses as follows: In the month of Chet, contemplate on God and unlimited joys will come. On Wednesday, let the light of God illuminate your intellect. Such interpretation is a mockery. What does one do on Monday? Darken one’s intellect? What about the non-Chet months? No need for contemplation? Or no unlimited joy anymore? Why only in Chet month?

If the point that Barah Maha Banee is not about the 12 months, and Vaar Banee is not about the 7 days, and Din Raen Banee is not about day and night is still not clear, then the following may help.

Elsewhere in the GGS there is a banee titled Pattee Likhee (Literally: the written alphabet). It has one paragraph devoted to each of the 53 then prevailing alphabets. (Rag Asa M: 1 Pattee Likhee GGS page 433). On page 435 there is another banee by Guru Amardas with the same name (Rag Asa M: 3 Pattee). On page 250 there is a banee by Guru Arjun called Bawan Akhree (52 alphabets). On page 340 there is a banee by Bhagat Kabir by the same name (Rag Gauri Purabi Bavan Akhree). Applying the logic of the sangrandees, are we now to say that these banees are about alphabets, that certain alphabets are auspicious (for use in our names for instance), or that certain alphabets are bad, or that certain alphabets require the intervention of certain chants and rituals to make them good. The beauty of these banees lies in the Guru’s and Bhagat’s spiritual creativity. Such ingenuity is so amply illustrated that they are able to advocate a different facet of God and His wonder in each and every one of the 52 alphabets. In one sense therefore the underlying message is that all the 52 alphabets are the same because one can always find something spiritual in each of them and all of them.

By advocating that a banee titled Twelve Months is about celebrating sangrand, the sangrandees have undertaken a great leap of logic. Such logic results if one takes the title and confers a meaning to suit a distortion. The meaning of the title should be inferred from the essence of the banee. On page 917 of the GGS we have a banee titled Anand. One could confer a distorted meaning to it by saying the banee was written for King Anand, or that it was written to express the Guru’s joy after his Anand (wedding) or that it was meant for his son named Anand.. The true meaning of “Anand” as ‘spiritual joy’ can only be inferred from reading and understanding the 40 paragraphs of this banee. The inferred meaning of Sukhmani in terms of ‘spiritual calm’ comes from understanding the 24 astpadees. The conferred (distorted) meaning of Sukhmani is “giver of sukh.” This meaning is distorted because in gurmat sukh and dukh are two sides of the same coin. GGS on page: 57 Sukh Dukh Sam Kar Janeyeh. In Sukhmani : Sukh Dukh Sam Dhristeta. (Sam means equivalent). The Guru could not be saying “sukh and dukh are the same, but then here is one banee (Sukhmani) that will bring you only sukh.”

The meaning of the title ‘Twelve Months” has been conferred by Sangrandees as follows: “sangrand is to be celebrated by Sikhs as an auspicious day on which they need to gather at the gurdwara to get guidance on how to spend the 30 days of a particular month. Now consider this: the word sangrand does NOT appear even once in both Barah Mahas. It does not appear even once in the entire GGS. To talk about 12 Indian months and NOT mention sangrand at all is the strongest critique of sangrand and its philosophy. The names of the 12 months are deployed in poetic manner to cajole the Sikh to link to God The message: “link to God/remember Him/sing His praises ” is the same for all the 12 “months.” Under such circumstances, the inferred meaning of Twelve Months ought to be: remember God irrespective of the month, day or hour. Another inferred meaning is: the months may have different names, but that Guru’s message is one and the same. In each and every one of these names lies a Godly message. Looked at from such perspective, Barah Maha is a banee, just like all other banees, for all occasions, NOT tied to any single day, and above all spiritually enlightening.

THE MESSAGE OF BARAH MAHA. Guru Arjun’s compilation starts with the couplet:

Kiret Karam Key Veecharay, Kar Kirpa Melo Raam. Chaar Kunt Deh Dis Bhramay, Thuk Aiye Prabh Kee Dhamm.

Guru Nanak’s composition begins: Tun Sun Kiret Karam Purab Kamaiya. Ser Ser Sukh Suhama Deh So Tun Bhala.

There is similarity in the words. The verses mean that I have been separated from you on account of my deeds/actions (kiret karam). [Karam means labour.] I have looked for peace and solace everywhere (four directions and 10 continents), and come to you after being exhausted by this search.

Can this be the opening verse of any thing remotely connected to sangrand, let alone a call to celebrate that day? A sangrandee is expecting the Guru to tell him that his suffering is on account of the inauspicious month (and not his actions). He is further expecting the Guru to tell him what to do to turn the inauspicious into the auspicious, or at the very least when (what month, time, day) everything will suddenly become auspicious. But the Guru is telling him, auspiciousness has nothing to do with the time, day, and month. It has all to do with our kiret karam, meaning actions.

Now let us look at a sampling of the way in which the names of the Indian months are elevated to mean more than just the name of the so called month. The reference to the name of the month is in bold.

A few points to ponder: The Guru changes the names of some months. Cheter becomes Chet, Bhadon become Bhadoey, Maghar becomes Manghar and Fagun becones Falgun. This is an indication that the Guru is not solely concerned with the month. If the month was or primary importance its name would not be altered. And if the objective of the verse or paragraph was to refer to the month, the month’s name would not be altered. Why change the name of something if the intention is to refer to that something? But if the objective is to give the word spiritual meaning, it could be changed accordingly. Also look at the verse Sawan Tina Suhagnee. If “Sawan” was nothing more than the name of the month, this verse would have to read “Sawan Tina Suhagana.” The names of the month is masculine. Also note that the Guru has place the word “Har” before Jeth. This indicates that the word “Jeth” is being referred to as an attribute of God (Har) and not purely as the name of the month called Jeth. The word “Jeth” is used to refer to an elder relative within family relations. Here “Jeth” as an attribute of God means “Supreme.” Of particular interest is Bhadon’s transformation into Bhadoey (Bha-do-ey meaning two fears or duality). A second verse of the Bhadon para reads Bhadon Bharam Bulaneay. Here Guru ji is clearly indicating that Bhadon means Bharam which means duality). The word Sey, before Bahadoey refers to “those.” So Sey Bhadoey means “those who have duality.”

The concluding verse of Guru Arjun’s Barah Maha is: Maha Devas Moorat Bhalley, Jis Ko Nadar Karey. Nanak Mangey Daras Daan, Kirpa Karo Harey. Auspicious are the months, days and moments for whosoever God casts His glance of grace. (Nadar Karey). Nanak seeks the blessings of your meeting; please shower Your mercy on me.

The concluding verse of Guru Nanak’s Barah Maha is: Bay Dus Mah Rutee Thitee Vaar Bhaley. Gharee Moorat Pal Sachey Aiye Sehej Milay. The 12 months, the seasons, the weeks, the days, the hours, the minutes are all auspicious when the Lord comes and meets me with natural ease.

In between the opening verse and closing stanza, Gurus Nanak and Arjun deliver a spiritually elevating discourse on our actions, on separation, on His blessings, His grace, His vision, His mercy, on remembering Him, on searching Him and on meeting Him with natural ease. Indirectly every one of these discourses cuts through the underlying, obsolete and archaic philosophy of sangrand (and everything else connected to it) like a hot knife slicing butter. The beliefs of sangrand are pulverized to dust and grounded to ashes within the mind of the Sikh who cares to understand the messages of Barah Maha. The false but powerful hold of fake commanding priests who used the pretense of celestial bodies to mislead and misguide lay people are all shattered by the messages of Barah Maha. In its place and within the Sikh mind, these two banees construct the purest and holiest of visions of the continuous grace and mercy of the Lord.

Yet if the sangreandee is bent on linking Barah Maha to sangrand, then the only link is that these two banees have with sangrand is that they provide a stinging critique of the philosophy of sangrand. Even then the critique is indirect, because both Barah Mahas make no mention of sangrand, the need for it, or for celebrating it. That is because neither of these banees is about sangrand.

THE REMAINING JUSTIFICATIONS. In the course of trying to educate the Sikh about Barah Maha, one faces weaker but no less erroneous justifications (mentioned as justification (iv), (v) and (vi) above. Brief responses to each are provided as closing statements of this article.

Sangrandees have argued that sangrand is just an occasion for sangats to meet and pray. It provides an added excuse to come to gurdwara. This argument obfuscates their choice. The following analogy will illustrate. Christmas day, simply because it is a holiday provides an added excuse for Sikhs to come to the gurdwara and do kirten, katha, ardas and sewa. No doubt about it. But if the gurdwara program (on Christmas day) went something like this: the reciting and singing of a specific banee or shabad that was said to be “connected to Christmas” or to the ideology of the occasion, a katha on Christmas, and an ardas for Christmas to bring joy - then the accurate explanation for such a practice would be that the gurdwara was being used as an excuse to celebrate Christmas. Sangrandees are thus guilty of using the gurdwara and gurbanee as an excuse to propagate, practice and instill the significance of a concept that has been absolutely discarded by our Gurus. They are seeking an excuse to celebrate Sangrand.

When parbhandaks and granthis are taken to task to explain their decision on sangrand, we are often told that they are acting on requests from the sangat. That the sangat is guru roop and therefore its request cannot be denied. What about those taking such parbhandaks to task – are they not the sangat as well? Such arguments are pathetic and reflect the pitiable state of our gurdwara leaders. Of what purpose are leaders if they have no spine to stand up for gurmat practices in the face of Bipran Kee Reet requests. The very least any parbhandak /granthi can do, if and when faced with such requests is to refer to the Sikh Rehat Maryada (SRM). The SRM advocates the celebration of Gurpurabs and four spiritual sanskaars (birth, anand karaj, death and amarat sanskar) in the gurdwaras.

All we need to ask is: Is sangrand a Gurpurab? Is sangrand any of the SRM mentioned Sikh sanskaars? The answer is clearly in the negative. But if our parbhandakhs still find it difficult to convey this fact to their sangats, then they may simply refer their sangats to the sub section on Gurdwara, page 12 para (h) of the SRM which advocates that non-Sikh celebrations should not be celebrated in the gurdwaras.

What is most detrimental about this particular Bipren Kee Reet called sangrand is that it the point of conception of all that needs to be thrown out of the Sikh psyche. Bringing sangrand into our gurdwaras is the start of the slippery slope towards everything else that needs to be thrown out. Sangrand is the Bipren door, that once opened, will cause a tirade of wayward practices to tip-toe in, each at the heels of the other. And that is because everything else: puranmashee, masia, lohree, karva chauth, maghi, rakhree, shraad – the list is endless – is conceived of sangrand and all that sangrand stands for. Sikhs need to link with the messages of Gurbanee or risk being de-linked from the Guru forever. End.

The author can be reached at [email protected]. Gursikhs wanting soft copies of the article for distribution in their Gurdwaras/sangats or posts on personal websites are welcome to request the same from the author.

[1] Other similar functions include Maasiya, Puranmashee, Lohree, Maghee, Rakhree, Shraad, Karva Chauth, Dushera and Divali etc. Divali is discussed in a separate article that appeared in this publication. This article concentrates on Sangrand, but will touch briefly on these other functions.

[2] These are: Chet, Vaisakh, Jeth, Haar, Sawan, Bhadon, Assu, Kathak, Magghar, Poh, Magh and Fagan.

Gurdwara Sahib

Woolwich is a non profit organisation founded on the universal

principles of Sikhism and dedicated to serving the Sikh community. All

rights reserved.

www.woolwichgurdwara.org.uk

www.woolwichgurdwara.org.uk